Since before

Crick and Watson, people have been dreaming about making changes to the human genome. First of all, watching a child die from

an inherited disorder is heart-wrenching. Most parents and physicians would do almost anything to

change that child's destiny. Then, the knowledge that many adults get sick and die prematurely, lose their strength and

their minds prematurely, leads many physicians and scientists to think about

changing the genes that cause that early decline. Finally, the knowledge that the degenerative changes of most common disease, including cancer and heart disease--and of aging itself--are

moderated by genetic processes, led many scientists to think of

adjusting the genetic compliment routinely.

With the discovery of

restriction enzymes and practical methods of

gene sequencing, the race to map the genes was on. It was important to understand the normal

human genome before scientists could identify the

genes that led to disease. Once all the disease genes were identified, it was thought that perhaps substituting healthy genes for the

disease genes might cure the underlying problem.

But the story was not that simple.

Early attempts to introduce genes into human subjects met with

unforeseen obstacles. And when it was discovered that there were only 25,000 to 30,000 human genes--instead of the expected 100,000--it began to dawn on scientists that there was more to the story than just the genes.

Epigenetic factors play into gene expression, which complicated the plot significantly.

Protein interaction, gene

regulator proteins,

non-coding RNA, and

glycomics--

among other

things--influence

gene expression and the ultimate fate of the cell. Of course, in humans, cells exist within tissues, tissues within organs, and organs within the human organism. Complex interactions occur at every level.

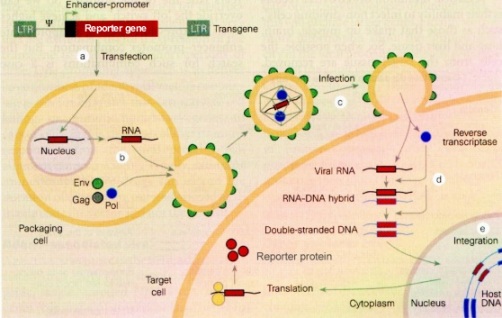

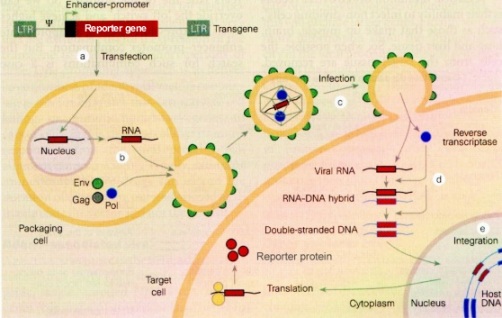

To introduce new genes into a cell with defective genes, you must have a vector. Gene vectors are

typically viral, since

viruses make a living by introducing their genes into an animal cell for its own replication. There are also

non-viral vectors that can be used to introduce genes into cells. Viruses have a billion+ year advantage as gene vectors, but

nonviral methods are improving

despite the challenges.

Besides introducing genes into cells, modern gene therapy also involves silencing of genes by

various means. Sometimes it involves activating dormant genes that are already present. And sometimes it means

delivering the entire cell--

genes, nucleus, cytoplasm, and all.

Human Gene Therapy journal has made

an entire issue freely available on the internet. The

latest news on gene therapy is

available through

various sources. A recent article in The Scientist discussed

future directions of gene therapy.

The

SENS approach to life extension involves interventions against seven causes of aging: Cell depletion, Unwanted Cells, Chromosomal Mutations, Mitochondrial Mutations, Protein Crosslinks, Extracellular Junk, and Intracellular Junk. None of them are insurmountable, and much of the new knowledge from molecular biology, stem cell biology, cell biology, and other areas of biotechnology, are applicable to these challenges.

The very proliferation of new knowledge in all of these areas present a difficulty.

Bioinformatics has evolved to

keep track of the impossible quantity of data being generated, but what is actually needed is a super-human intelligence to make sense of it all, and to prioritise new research. In lieu of that, we will have to muddle through. Bit by bit, we seem to be succeeding. It would go much faster with some next-level supervision, but such is life.

Labels: gene therapy, genomics, micro RNA